This week’s Page by Page post is a little bit different. Normally, I share advice, experience, and encouragement here, in order to help others get the most out of their work as writers, scholars, and teachers.

This week, I want to remember the person who put me on the path I’m still following today: Mr Colin Wilcockson (1932-2023).

It was last Wednesday night when I saw the announcement.

I was scrolling through Twitter in bed, as I often do, at the end of a very rough day. And that was where I saw the tweet from Pembroke College, Cambridge:

The college is saddened to announce that Emeritus Fellow Colin Wilcockson (1973) has died, aged 90.

The thoughts of everyone at Pembroke are with his widow Pam, sons Michael, Nigel, and David, and the wider Wilcockson family.

My heart sank when I read the words.

Just the week before, I had been thinking of getting in touch with Colin. I wanted to hear how he was doing. I wanted to tell him that I was writing a couple of books on Chaucer. I wanted to let him know where I’d gotten in my life and career, thanks to him. But I never sent that email.

Late that Wednesday night, I sent out a tweet of my own, expressing my condolences. And then I put my phone down and cried.

The first time I ever heard from Colin was a little over twenty years ago, on 15 December 2000. I still have that email, which opened with a cheerful smattering of exclamation marks:

Dear Mary,

Wow! Things move fast! Alan Dawson mentioned you to me yesterday at about 2pm (our time), sent me a copy of his email to you, and here’s your response. Conveying messages in the Middle Ages was a little more leisurely and doubtless haphazard.

The cheerfulness immediately put me at ease. I was preparing to leave for a semester abroad at Cambridge in just a few weeks’ time, and I was anxious. I’d timidly asked Pembroke’s ‘International Programmes’ department whether there was any way I could study medieval literature while I was there. No sooner had I asked my contact at the college, Dr Alan Dawson, than I received a lively message from Colin offering me a menu of medieval study options to choose from.

The same sprightliness and warmth would accompany every interaction I had with Colin from that moment onward.

This included our first meeting in person.

I was cowering in Dr Dawson’s office, on the verge of a panic attack (what had I been thinking?! I didn’t belong in a place like Cambridge!!). Clearly feeling the need for reinforcements, Dr Dawson telephoned across to Colin’s office. The conversation was not on speaker, but I could hear the energetic voice on the other line from all the way across the room.

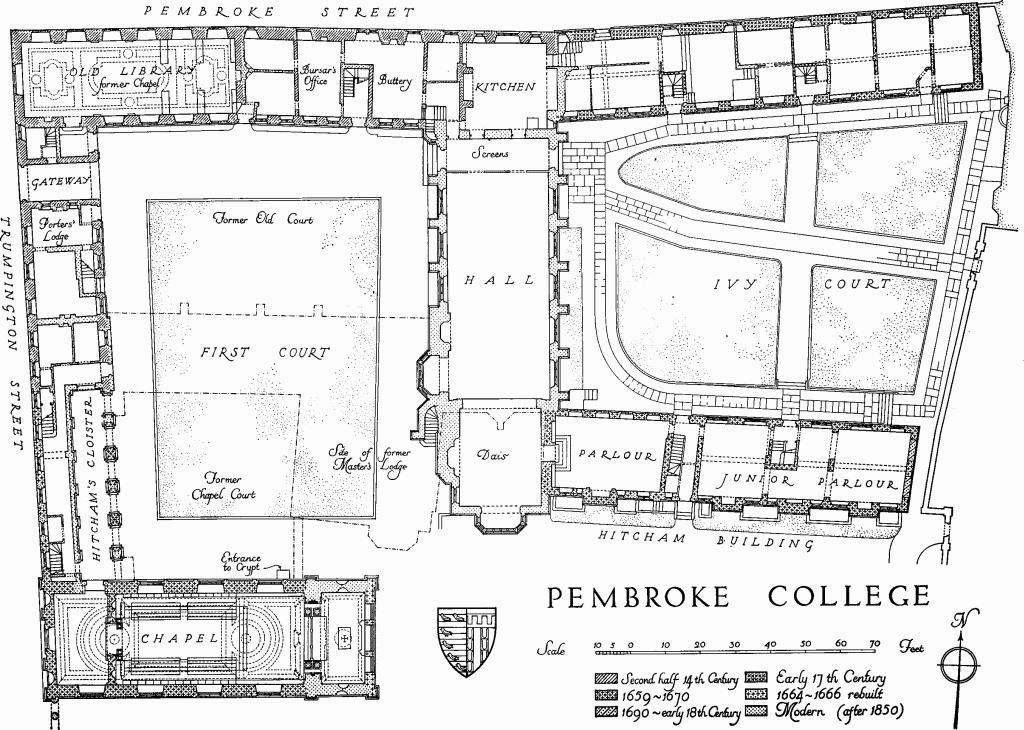

After hanging up, Dr Dawson informed me that Colin was coming down to the college’s fourteenth-century front courtyard to meet me.

I had barely set foot in Old Court when a white-haired gentleman in a sweater and corduroy trousers swept out of a nearby staircase and clasped me by both hands: ‘Mary Flannery—how lovely to meet you!’

Suddenly, everything was all right.

When I think of Colin, I remember his kindness, warmth, and generosity. I also remember twinkling blue eyes, a quick sense of humour, and the most expressive reader of Middle English I have ever known.

Colin was a scholar and a poet, but he should have been a bard. Anything he read aloud sprang to life in the room, conjured up by his voice’s shifting tones and by the expressions on his face. It came naturally to him, but it was also his craft; he himself seemed to be aware of—and, I think, even a little pleased by—the effect his reading could have on listeners.

There was one passage in particular that he loved to read aloud to students: Malory’s account of the final meeting of Lancelot and Guinevere at the end of Le Morte D’Arthur. Colin’s reading of this passage moved more than one student to tears (I was one of them, and I was so impressed by the experience that I invited friends to join me for another one of his readings).

When I look back at the term we spent together, I still sometimes feel like I had no business studying Middle English with a brilliant supervisor like Colin at a place like Cambridge. What had I been thinking?! Up to that point in my studies, I had only ever read medieval literature in translation. Anyone who has ever encountered Sir Gawain and the Green Knight in its original dialect and orthography will be able to imagine the panic I felt the first time I looked at Tolkien’s edition of that text in Colin’s office.

But in that book-crammed room at the top of a stone staircase, I read Sir Gawain, Troilus and Criseyde, and the Parliament of Fowls in Middle English for the very first time, accompanied by Colin’s melodious recitations from those centuries-old poems.

I remember the awe I felt when I saw that Colin had edited The Book of the Duchess for The Riverside Chaucer, the edition I have used in my research and teaching ever since. When I asked him about it, he happily drew my attention to the fact that his edition of the poem for the Riverside was accompanied by a woodcut image of a hart, the animal at the heart of the poem’s consolatory wordplay: al was doon, / For that tyme, the hert-huntyng. Colin was the perfect editor for that charming and wistful poem.

I’ve been fortunate enough to have learned from many great medievalists in my time, but it was Colin who taught me to love medieval English literature. He was the reason why I wanted to return to Cambridge to study medieval English literature for my masters (and, eventually, my PhD). In some ways, though he only taught me during one cold Lent Term, he made me the teacher I am today.

Colin and I stayed in touch during and after my graduate studies. Every time we bumped into one another in college or on the street, he would greet me with the same warmth he’d exhibited the very first time we met (‘Well, hello!’). During one of his holidays away with Pam, I looked after the chickens they kept in their backyard. (I was so terrified the chickens might escape that I opened the door to their coop as quickly and narrowly as I could whenever I visited them, lest ‘Pertelote’ make a break for it.)

When I left Cambridge, our correspondence dwindled, though I followed his work as the editor of the ‘Gossip’ pages in the Martlet, the college’s alumni magazine. His editor’s note makes me smile even now:

Gossip should be sent to me by email[.] …Alternatively, send by post[.]

I wish I could have thanked Colin one more time for the gifts he gave me. I wish I could have shared with him my own stories of teaching medieval English literature. But more than anything else, I am so very, very grateful to have known him. And so, like the narrator of Chaucer’s Book of the Duchess, I have tried to put that gratitude into words, as I kan best.